Flexible proteins for assembling viruses: from disorder to symmetry

Researchers have explained the mechanism by which identical proteins manage to organise themselves and form the perfectly symmetrical capsids of most viruses

References :

Siyu Li et al., From disorder to icosahedral symmetry: How conformation-switching subunits enable RNA virus assembly. Sci. Adv. 11, ealy7241 (2025).

DOI : 10.1126/sciadv.ady7241

Open archive HAL

Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) viruses represent the largest and most diverse family of viruses known, affecting humans, animals and plants. Their formation is based on a fascinating phenomenon: hundreds of identical proteins spontaneously self-assemble to form the protective shell of the virus, called the capsid, often adopting an icosahedral symmetry of remarkable precision. However, despite decades of research, the physical and molecular mechanisms governing this self-assembly remained poorly understood.

The present study was carried out in the following CNRS laboratory:

Laboratoire de physique des solides (LPS, CNRS / Université Paris-Saclay)

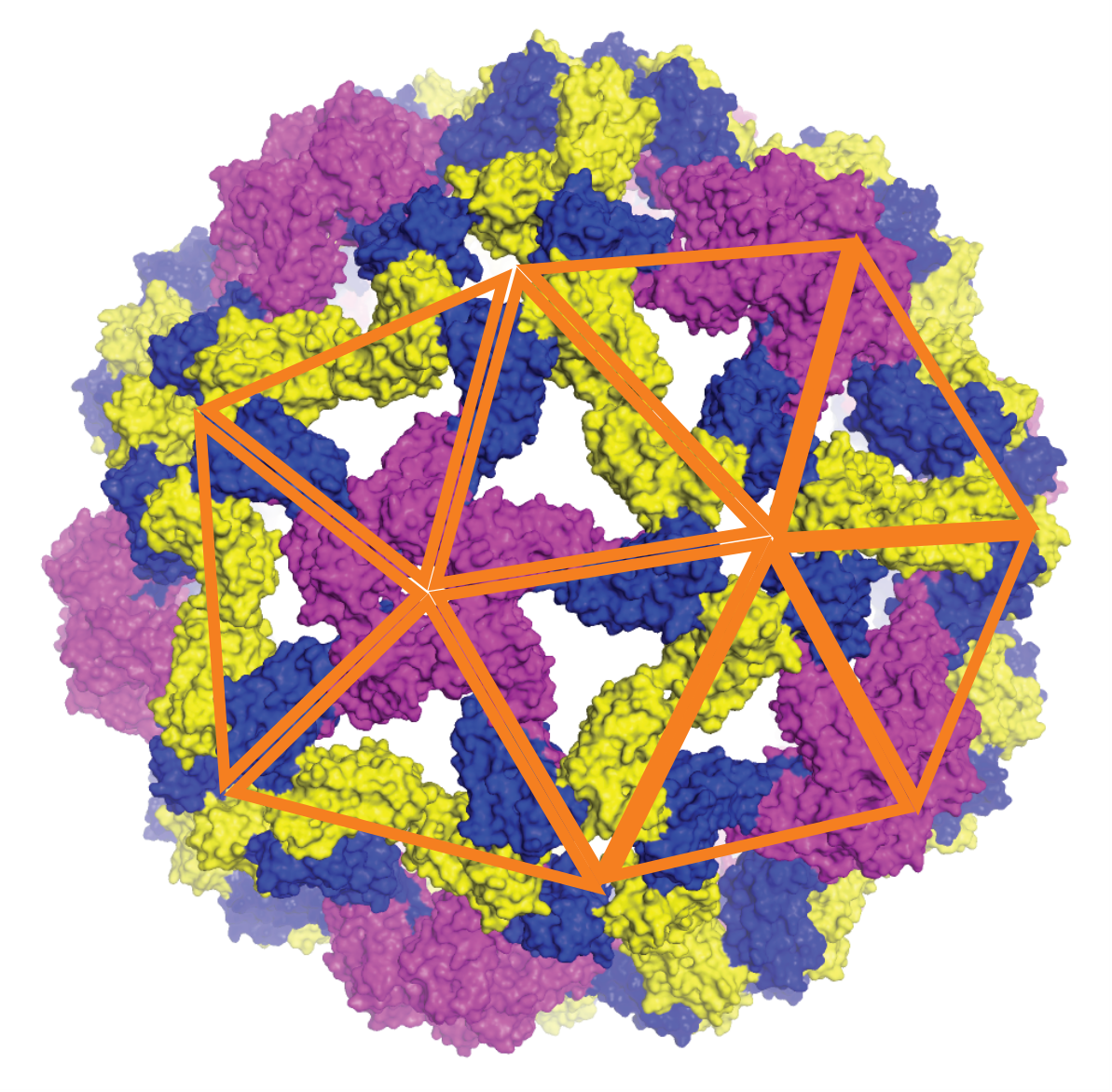

To elucidate this process, researchers from a Franco-American collaboration involving the LPS developed an innovative molecular dynamics model combining essential elements of physics and biology, namely protein diffusion, viral genome flexibility, and a conformational switching mechanism mimicking allostery, the ability of certain proteins to change shape when binding to the site of an effector molecule (which may belong to the same protein). In this model, each protein subunit is capable of changing shape when it interacts with another, activating elastic properties that facilitate the construction of a regular shell. This flexible behaviour – absent from previous rigid models – makes it possible, for the first time, to digitally reproduce the spontaneous formation of complete icosahedral capsids corresponding to the ‘T=3’ and ‘T=4’ structures most commonly found in nature.

Simulations show that assembly does not follow a single path but occurs via several parallel pathways: shell fragments appear simultaneously at several points in the genome, then fuse and reorganise until they achieve a perfectly symmetrical structure. This dynamics ‘from disorder to symmetry’ reveals the key role of protein flexibility in overcoming the energy barriers that separate unstable states from ordered viral architectures. These results have been validated experimentally using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) measurements on the plant virus CCMV (Cowpea Chlorotic Mottle Virus). The researchers showed that the secondary structure of RNA strongly influences the success of assembly: more branched, and therefore more compact, RNAs promote the formation of complete shells, while more linear RNAs lead to incomplete or irregular structures.

By demonstrating that viral symmetry emerges from universal physical principles —a subtle balance between elastic properties, electrostatic forces and genome architecture— this work represents a substantial advance in our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of virology. This approach provides a general explanatory framework for understanding capsid formation and stability, opening up new perspectives for the design of artificial nanocapsids for encapsulating therapeutic molecules or for the design of antiviral agents targeting the early stages of viral assembly. These results are published in the journal Science Advances.