To thoroughly soak a hydrophobic material, better use a paste than an ordinary liquid!

By visualising the passage of a complex fluid through a hydrophobic mesh, physicists have shown that a water-based paste penetrates much more evenly than water, a counterintuitive observation that could, for example, lead to better control of the forced imbibition of mortar into external insulation panels.

References:

Capillary and priming pressures control the penetration of yield-stress fluids through non-wetting 2D meshes. Manon Bourgade, Nicolas Bain, Loïc Vanel, Mathieu Leocmach & Catherine Barentin, Soft matter, publié le 26 septembre 2025.

DOI : 10.1039/D5SM00759C

Archive ouverte arXiv

When a sponge comes into contact with water, the liquid will spontaneously penetrate the pores of the sponge through capillary action because they are hydrophilic. However, if instead of water we want to soak up a thick sauce, the absorption will be slower or even only partial, due to the more complex flow properties of the fluid. Sometimes we want to force a fluid into a material whose pores are not spontaneously wetted by the fluid, for example to dye or wash a fabric, or to use mortar to stick hydrophobic mineral wool panels used in building insulation. In this case, we know that capillary forces resist wetting, and that sufficient pressure must therefore be applied for the fluid to begin to penetrate.

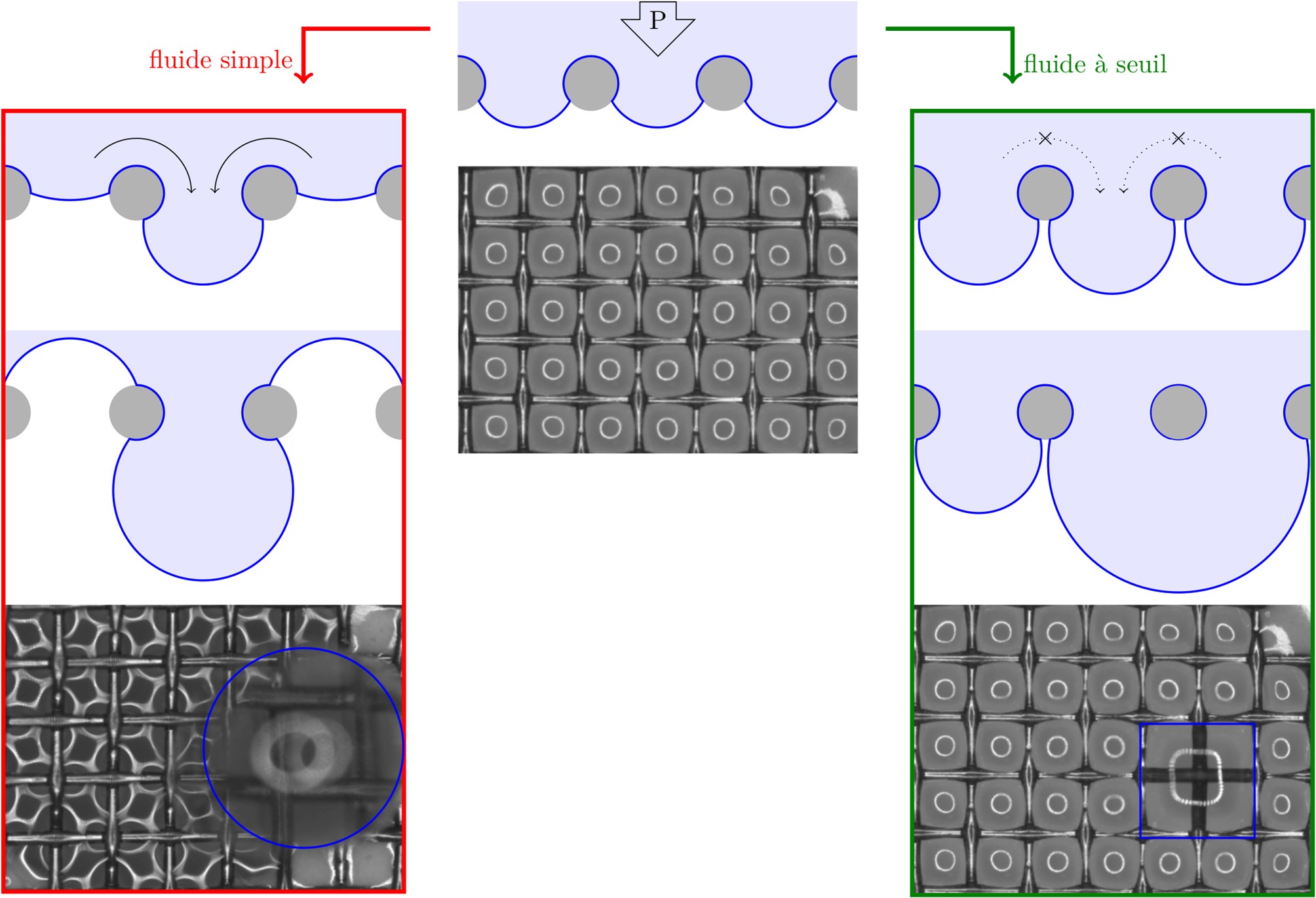

In the case of a simple fluid, the problems do not end there: the fluid penetrates in a very uneven manner, advancing along the easiest path and completely avoiding the majority of the pores. In the end, only a very small part of the material is actually wet. As in practical applications of wetting, most of the fluids we want to penetrate are complex, so understanding how the flow properties of the fluid change the behaviour of forced wetting is a major industrial challenge.

As in the case of a sponge, a complex fluid is expected to resist more than a simple fluid. Take the case of a ‘threshold fluid’, typically a paste that only flows when sufficient stress is applied, such as toothpaste or fresh mortar. By definition, if a hydrophilic porous material is filled with such a threshold fluid, flow can only occur if pressure greater than a threshold pressure is applied. As a result, this flow can be very inhomogeneous, with areas where the stress is low and there is no flow at all. One might therefore think that forced imbibition of a threshold fluid into a hydrophobic porous material would be more difficult than with a simple fluid, resulting in an even less homogeneous outcome.

The present study was carried out in the following CNRS laboratory:

Institut lumière matière (ILM, CNRS / Univ. Claude Bernard Lyon 1)

A group of physicists from iLM (Lyon), in collaboration with Saint Gobain Recherche (Aubervilliers), has debunked these preconceptions through model experiments involving the penetration of a paste through a hydrophobic mesh. They applied pressure to force a model water-based threshold fluid through a hydrophobic mesh (mesh size approximately 100 µm) and observed the passage under a microscope. By changing the geometry of the mesh and the threshold stress of the fluid, they observed that the pressure required to observe flow is mainly determined by capillary effects, and very little by the threshold. Paradoxically, the fact that the fluid has a threshold does not make penetration more difficult!

On the other hand, it turns out that the phenomenology of passage is completely changed by the threshold. Whether for a simple fluid or a threshold fluid, the latter begins to penetrate all meshes in parallel. But the slightest defect in the mesh – for example, a slightly wider mesh, or a lack of hydrophobicity – allows the material to pass preferentially through one mesh to the detriment of the others. In the case of a simple fluid, this leads to an unstable situation where the fluid passing through this defect forms an increasingly large drop that sucks in the surrounding fluid, thus emptying the neighbouring meshes. In contrast, in the case of a paste, the existence of a flow threshold prevents the first mesh from taking precedence over the others and forming a preferential ‘route’ for the fluid to flow. The situation is therefore stabilised, and the fluid flows in parallel through all the meshes. The droplets passing through neighbouring meshes eventually touch each other and coalesce beyond the mesh. Thus, through coalescence after coalescence, homogeneous forced imbibition is achieved.

By expressing the stabilisation criterion provided by the existence of the threshold constraint in equations, the researchers also showed that, over a wide range of parameters, the pressure required for a threshold fluid to penetrate is not significantly higher than in the case of a simple fluid. This work thus makes it possible to rationalise many industrial situations where it is necessary to penetrate a paste into a non-wetting porous material: textiles, cosmetics, construction, etc. Taking a step back and understanding the fundamental physical ingredients opens the door to more efficient processes and technologies, particularly for building insulation. This work is published in the journal Soft Matter.